No doubt at some point you’ve looked up at the clouds, if just for their beauty, and to marvel at the different shapes and sizes. By knowing the various cloud types you can make general assumptions about current and near-future weather.

Cloud formation occurs just about anywhere in the troposphere: fog is a cloud that has developed at the surface, and the highest clouds can reach altitudes of 75,000 feet. There’s even a recently-discovered cloud type that forms 250,000 feet above the earth’s surface, called noctilucent clouds, which scientists are still trying to figure out how they form.

Our focus is much closer to Earth. Meteorologists classify cloud types into three major groups by height (their elevation in the atmosphere), not how tall they are from top to bottom. There are ten major cloud types and about two dozen less common types. We can’t get to all of them in the guide, but we’ll cover the major ones.

Quick note: Cloud identification isn’t an exact science, especially since no two clouds are exactly alike. My meteorology professor pointed out that two meteorologists might have two interpretations, and both might be right. Your identification might differ from a fellow weather enthusiast or meteorologist friend. (I disagreed with my professor on one of his cloud quiz “correct” answers, so I know firsthand!)

What are the different types of clouds?

There are five primary cloud types, each with its subtypes. Fog is considered its own type, and then three cloud types are based on height: low, middle (mid-level), and high. Finally, there is a fifth type reserved for clouds that develop vertically: cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds are the only two cloud types in this category.

Fog

When the air is moist, evaporating moisture from the surface doesn’t have to travel very far to start condensing, and a cloud begins to develop near the surface. Called radiation fog, it develops as the ground loses heat generated by solar radiation and rises into the cooler air above it, condensing where the warm air meets cooler air and happens easiest on a clear, cool night. Clouds are a natural method for the atmosphere to retain heat gained through solar radiation, and without them, at night the Earth would lose that heat much more quickly, making for more severe temperature changes.

But that’s not the only way fog can form: it also develops when warm air passes over a cool surface, called advection. This type of fog is most common near cool bodies of water: the iconic fog of San Francisco is a great example. Advection fog can occur inland; along the Gulf of Mexico in the winter months, air passing over the normally warm Gulf waters streaks northward and over the relatively colder land of the southern United States, causing advection fog.

Elevation changes can cause fog on the windward side of mountains when moist air is pushed up the mountain slope causing it to cool and condense; evaporation fog occurs when cold air passes over warm water in the autumn months.

Low-Level Clouds

Low clouds give us our dreariest days, often blocking out much of the sun’s light and turning the landscape gray. Low clouds are less than 6,500 feet from the surface and are primarily comprised of liquid water.

Stratus

The basic low cloud type is the stratus cloud, and it covers the entire sky. It’s essentially fog that doesn’t touch the ground: as fog lifts, it sometimes remains as a low stratus cloud. No precipitation typically falls from stratus clouds, although if it does it is in the form of drizzle.

Nimbostratus

Nimbostratus. These clouds are typically accompanied by lower wispy clouds, which are called fractus.

Often confused with the stratus (and vice versa) is nimbostratus. One key difference here is the heaviness of the precipitation that falls. If it is light to moderate (heavier than a drizzle), the sky is uniformly gray, and difficult to discern any cloud formations, then the cloud is nimbostratus. Visibility below these clouds is also typically poor, as precipitation evaporates as it falls.

Stratocumulus

Low, lumpy clouds with patches of blue sky between them are stratocumulus. These clouds rarely produce precipitation, and you can tell the difference between this cloud and its higher brethren altocumulus by extending your hand and pointing to the cloud. If it is close to the size of your fist, it is stratocumulus.

Mid-Level Clouds

Clouds that form between 6,500 and 25,000 feet above the surface are known as middle or mid-level clouds. These clouds may serve as a warning of impending bad weather. They are typically still comprised of water droplets, but in cooler weather can be mixed in with ice crystals.

Altocumulus

Small, puffy clouds in the mid-levels are called altocumulus. They’re typically found in waves or bands. On humid summer mornings, if altocumulus appears as the day goes on, there is a better chance for afternoon thunderstorms. If you’ve ever heard the term “mackerel sky,” it refers to these types of clouds. When in long rows, they appear much like fish scales – thus the name. When cirrus appears like this, you can typically expect rain within the next 8-10 hours.

Altostratus

Hazy days when the sky is gray and the sun is dimly visible indicate the presence of altostratus. These clouds typically form out ahead of a widespread and continuous area of precipitation, and if they begin to lower, can produce precipitation.

High-Level Clouds

High clouds are typically wispy, small clouds that form above 20,000 feet, are quite thin and are comprised primarily of ice crystals. Their presence is typically associated with fair or pleasant weather. Sometimes they also may provide warning of incoming rain or snow.

Cirrus

The most common of the high clouds is the wispy cirrus. Its presence in the sky is typically associated with fair and pleasant weather, but it also can form far out ahead of an approaching frontal system. Occasionally they precipitate, but this precipitation evaporates before it reaches the ground, creating fallstreaks.

Cirrocumulus

Cirrocumulus among some cirrus clouds.

Much less common than cirrus is the small puffy cirrocumulus. These are exceedingly rare and can be confused with altocumulus. However, these clouds are typically very small, due to how high they are in our atmosphere, and can be mixed with other cirrus cloud types, as we see above.

Cirrostratus

High, thin sheet-like clouds that cover the entire sky, yet allow the sun and moon to be seen clearly, are cirrostratus clouds. They’ll typically form well out ahead of a storm system and can precede precipitation by 12 to 24 hours. Cirrostratus clouds also cause a large halo around the sun during the day, and the moon at night.

Clouds with Vertical Development

Two cloud types fall outside of the standard classification by elevation in the atmosphere. They are distinguished by how tall they are. These clouds form generally closer to the ground but can be tens of thousands of feet high.

(I’ve also included a few additional cloud subtypes associated with these clouds, too).

Cumulus

The puffy cumulus is the cloud shape that most of us picture, with its cotton-ball–like appearance and fairly large size. On days when the clouds do not get overly tall, they are a sign of fair weather (thus the name ‘fair weather cumulus’). If these clouds grow larger vertically, they can cause precipitation, although it’s generally showery in nature.

Cumulus congestus

Cumulus congestus is a type of cloud that is commonly associated with towering, cauliflower-like formations in the sky. These clouds are often seen on warm and humid days, and they indicate the potential for thunderstorms. Cumulus Congestus clouds are characterized by their vertical development and can reach impressive heights. They are known for their dark, flat bases and fluffy, billowing tops. These clouds are a visual representation of the convective activity happening within the atmosphere and serve as a sign of atmospheric instability. When you spot Cumulus congestus clouds, it’s a good idea to keep an eye on the sky for potential thunderstorm development.

Cumulonimbus

Cumulonimbus cloud, with its trademark anvil. If a tall cumulus cloud continues to grow vertically, it will turn into a cumulonimbus cloud, and begin to produce lightning. These clouds can grow to 60-70,000 feet high, and with height will show a more pronounced area where the cloud starts to spread out, called an anvil. Cumulonimbus and the thunderstorms they produce are associated typically with strong winds, heavy rain, and occasionally hail and tornadoes.

Wall cloud

A wall cloud is characterized by a large, lowering, and rotating cloud base that appears like a wall hanging from the main storm cloud. Wall clouds are typically found in the vicinity of supercell thunderstorms, which are known for their intense updrafts and potential to produce tornadoes. These clouds can be dark and menacing in appearance, with a distinct shape that sets them apart from other cloud types. While not all wall clouds produce tornadoes, they are an important indicator of severe weather and should be taken seriously.

Shelf cloud

A shelf cloud often accompanies strong thunderstorms or squall lines. It appears as a low, horizontal cloud shelf extending outward from the base of a thunderstorm. Shelf clouds are typically dark and ominous in appearance, with a distinct wedge shape. They are caused by the cold air descending from the storm cloud and pushing warm air ahead of it, creating a noticeable boundary. Despite their intimidating appearance, shelf clouds are not typically associated with tornadoes or severe weather but can serve as an early warning for severe weather after it passes.

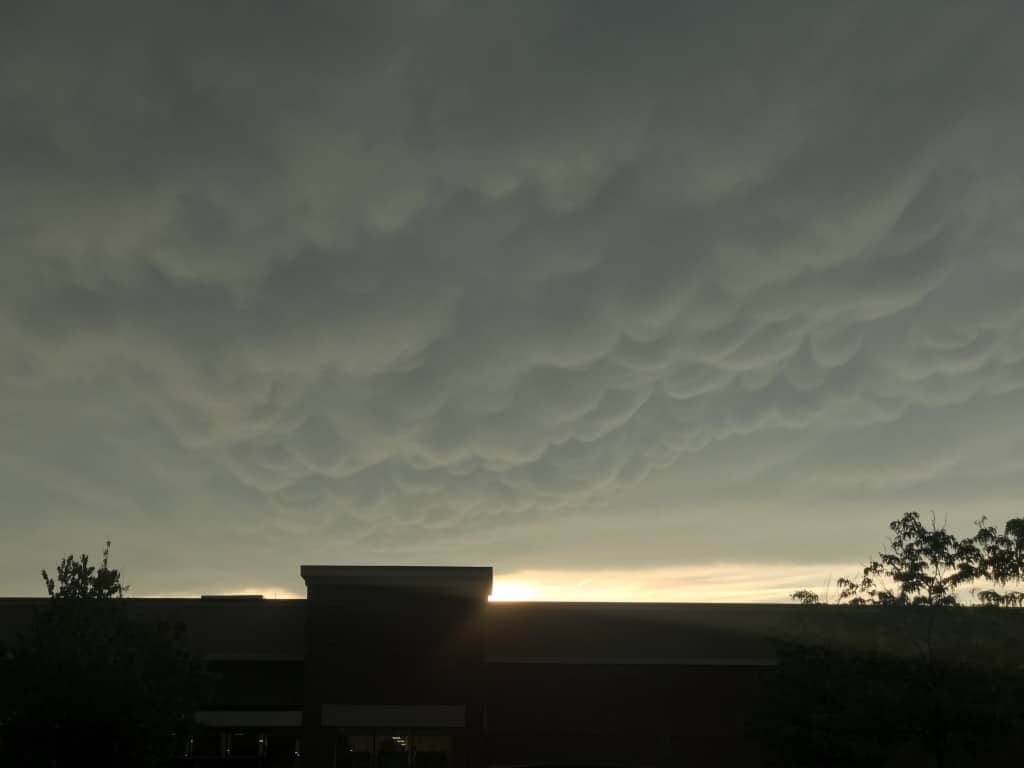

Mammatus

Mammatus clouds are characterized by their distinct pouch-like or bubble-like shapes that hang beneath the base of a cloud. Mammatus clouds are typically formed in the aftermath of severe thunderstorms or intense convective activity. They are often associated with the downdrafts of a storm system, which cause the air to sink. Mammatus clouds can appear in various sizes and colors, ranging from white to gray to even a reddish hue during sunrise or sunset.

Want to learn more?

This post is an excerpt from my book, Weather Watch: An Introduction to America’s Weather and Climate, available on Amazon, and free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers!

Experience the fascinating world of weather with the second edition of Weather Watch: An Introduction to America’s Weather and Climate. This book doesn’t just explain weather and climate concepts—it brings them to life.

Weather Watch is perfect for teenagers and adults who wish to deepen their understanding of the dynamic world of meteorology. Simplifying the complex, this book breaks down the science of weather into smaller, easily digestible concepts, allowing you to build on your knowledge with each chapter.

Here’s what to expect:

- Detailed insights on clouds, pressure and wind, reading weather maps, hurricanes, and tropical storms

- Enlightening discussion on climate change

- Essential guidance on purchasing a weather station

- Critical information on severe weather and tornadoes

- Learning how to forecast the weather yourself

This second edition comes completely reformatted with over 30 pages of new content, including advanced weather map analysis and space weather. It’s more visually appealing with additional illustrations and graphics. Each chapter now ends with handy links for more in-depth learning, and sprinkled throughout the book are captivating American weather events, serving as real-life illustrations of introduced concepts.