This summer marks three decades since the United States experienced one of its most significant and devastating natural disasters – the Great Flood of 1993. Affecting nine states across the Midwest and resulted in the loss of 50 lives, causing an estimated $15 billion in damages (approximately $30 million in 2023 dollars) and submerging 17 million acres of land in floodwater, in some places for over six months.

Few flood events have equaled the duration and severity of the Great Flood of 1993, either before or since. The flooding along the Mississippi was the worst since 1927, and in some cases, including the extent of flooding, it was significantly worse. The records set during the Great Flood have also proven resilient, with few records set that year exceeded in the three decades since.

The Great Flood resulted from a unique combination of meteorological factors, including persistent heavy rainfall and saturated soil from the previous winter’s snowmelt. The rain fell from April to August, inundating the Mississippi and Missouri River basins and causing rivers and their tributaries to overflow. The flooding was further exacerbated by the failure of numerous levees designed to protect communities and farmland from rising waters.

As we approach the 30th anniversary of the Great Flood, we revisit its causes and impacts, the lessons learned, and the progress made in flood management since the event.

Great Flood of 1993: How it Happened

Unlike most flood events which develop quickly and often end just as quickly, the Great Flood of 1993 was a slow-motion disaster. The seeds for this massive months-long event were set during the fall and winter before, during an El Niño that featured a zonal flow with fast-moving (and moisture-rich) low-pressure systems racing across the Upper Midwest.

Spring/Early Summer: A Slow-Motion Disaster Unfolds

The spring of 1993 continued the trend of above-average precipitation across large swaths of the upper Midwest. Combined with the melting of a larger-than-normal snowpack from a harsh winter, runoff rose water levels in rivers and streams across the region. Many areas would see the first floods by mid-Spring, although a relative break in the rain in late Spring allowed some rivers to briefly fall back below flood stage.

As the rain returned in June, more and more tributaries of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers began to flood, causing water levels to rise even further downstream. By early June many rivers were already at or near flood stage. On June 10, the Mississippi River at St. Paul, Minnesota, exceeded its flood stage and continued to rise.

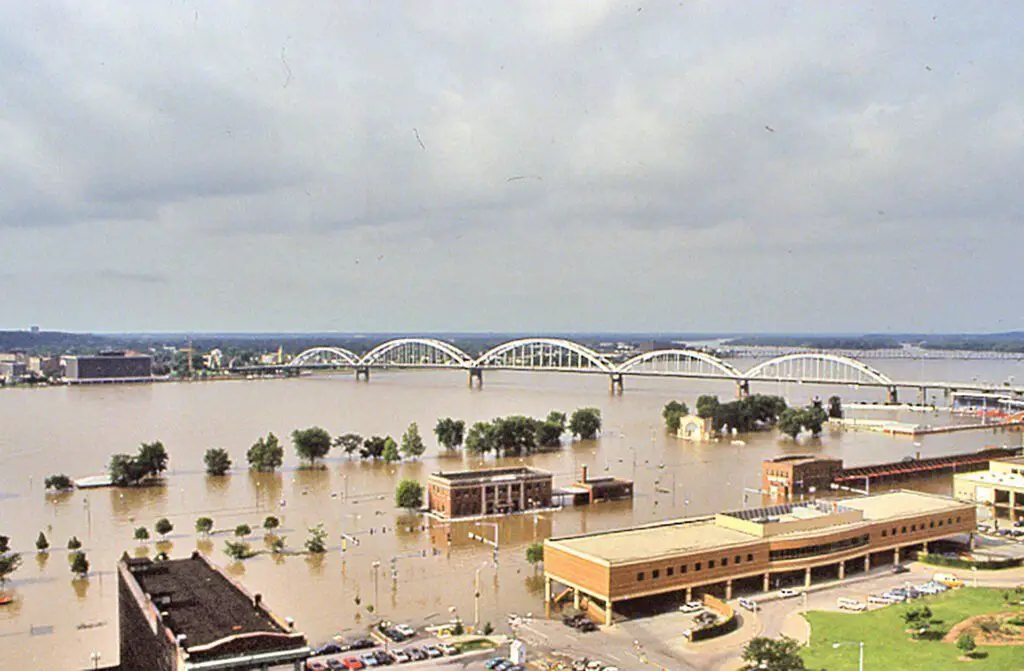

In Davenport, Iowa, the Mississippi River reached flood stage on June 16 and continued to rise rapidly, cresting at over 22 feet above flood stage on July 9. The city, which had no permanent floodwall then, saw extensive flooding in its downtown area, with many businesses and homes inundated.

Heavy rainfall in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, caused the Big Sioux River to overflow, evacuating hundreds of residents and closing major roadways. Communities along the Des Moines River in Iowa also experienced significant flooding, with the river cresting at record levels in several locations.

Mid-Summer: Unprecedented Flooding

July was the turning point for the Great Flood, as relentless rainfall continued to pound the Midwest. Neither the ground nor the region’s waterways had time to recover between deluges, causing creeks and rivers to rise dramatically. Many locations saw measurable rain on 20 days or more during the month.

Persistent rain wasn’t the only issue: the month featured flash flooding events caused by thunderstorms that dropped a half-foot of rain in a single day in some locations, especially across Missouri and Iowa.

By mid-July, the Mississippi River had reached record levels in several locations, with levees failing under immense pressure. One of the most notable levee breaches occurred in West Quincy, Missouri, on July 16, causing a massive flood wave that devastated the area and severed a major highway bridge. Many other levees were also breached or overtopped during this period, resulting in widespread flooding and evacuations.

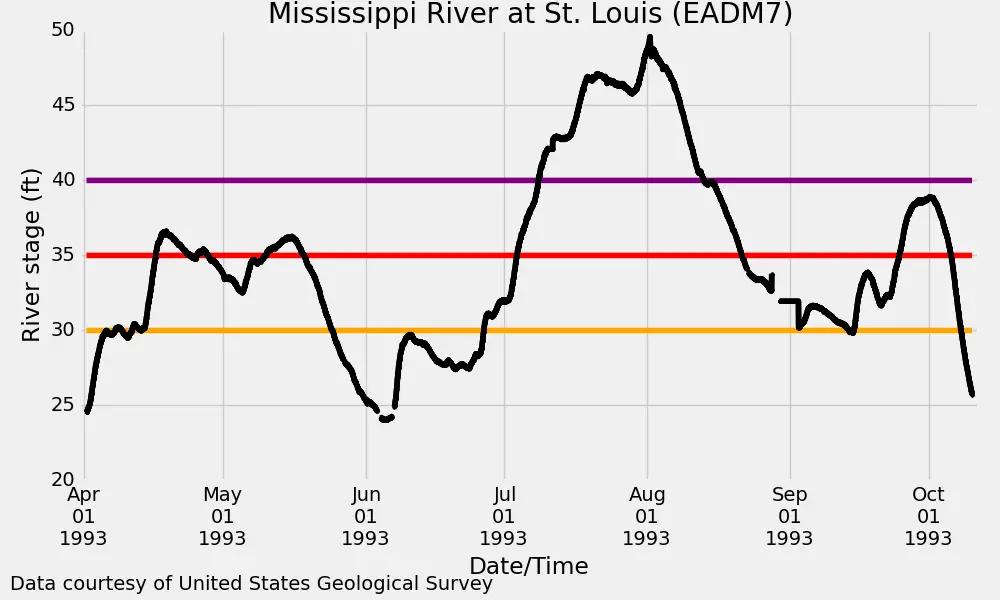

In St. Louis, Missouri, the Mississippi River crested nearly 20 feet above flood stage on August 1, a record crest. The city’s floodwall held firm, but the floodwaters inundated the historic riverfront district, causing extensive damage to businesses and infrastructure. Floodwaters surrounded the Gateway Arch and were temporarily closed to visitors.

Further north, in Grafton, Illinois, the confluence of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers saw unprecedented flooding, with the river cresting at over 16 feet above flood stage. The town was virtually submerged, with only a few rooftops visible above the water. Residents had to be evacuated by boat, and the community faced a long and challenging recovery process.

Late Summer/Fall: Slow Improvement

In August, the floodwaters slowly receded as the rains finally let up. However, the damage left after the flood was extensive, with thousands of homes destroyed, farmland inundated, and critical infrastructure damaged or washed away. Cleanup and recovery efforts were underway, but many communities remained inaccessible due to the lingering high water levels.

While a widespread region saw at least a foot or more of rainfall from April through August, the most significant rains fell in Iowa and nearby states. In a corridor roughly from northeast Kansas through eastern Iowa, 20″ or more fell, with some areas in eastern Iowa seeing as much as four feet of rainfall, a foot more than the region receives in an average year.

By the end of the summer and beginning of fall, some portions of the Midwest were underwater for six months. Grafton, Illinois, recorded flooding for 195 days; Clarksville, Missouri, for 187 days; Winfield, Missouri, for 183 days; Hannibal, Missouri, for 174 days; and Quincy, Illinois, for 152 days. The Mississippi also stayed above flood stage in St. Louis for 103 days, falling below on October 7.

The Great Flood’s Impacts

The Great Flood had far-reaching social, economic, and environmental impacts. Millions of acres of farmland were submerged, resulting in billions of dollars in agricultural losses and food shortages. Some affected farmlands took years to become suitable for farming again.

Thousands of homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed, displacing countless residents and disrupting local economies. The flood also took a toll on the region’s infrastructure, with roads, bridges, and railway lines washed away or severely damaged, impeding transportation and commerce for months. According to the National Weather Service, barge traffic on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers stopped for nearly two months, resulting in almost $2 million in daily losses.

Communities across the Midwest have taken steps to become more resilient in the face of future floods. This includes developing comprehensive emergency plans, investing in flood-resistant infrastructure, and creating public awareness campaigns to educate residents about flood risks and preparedness measures.

One of the most significant and challenging steps some communities took was relocating entire neighborhoods to higher ground. The process of relocating communities not only reduced their vulnerability to future floods but also fostered a greater sense of community and shared responsibility for disaster risk reduction. Examples of communities that underwent relocation after the Great Flood of 1993 include Valmeyer, Illinois; Rhineland, Missouri; and Pattonsburg, Missouri.

In the aftermath of the flood, the residents of Valmeyer, Illinois, boldly decided to relocate their town to higher ground. Approximately 90% of the community’s buildings were destroyed or severely damaged, making it clear that rebuilding in the exact location would be unwise. With federal and state funding support, the town was relocated to a bluff about two miles from its original site. The new Valmeyer was designed with flood resilience, featuring elevated homes and infrastructure to reduce the risk of future flooding.

Rhineland, Missouri, was another community that relocated after being devastated by the Great Flood of 1993. In a remarkable display of determination and unity, residents worked together to physically move some of the town’s historic structures to a new site on higher ground. The relocated town, dubbed “New Rhineland,” now sits about a mile away from its original location, safe from the threat of future floods. The town’s relocation is an inspiring example of community-driven resilience and adaptation.

Pattonsburg, Missouri, was another town that faced the tough decision to relocate following the flood. After 90% of the town was submerged under water, the community decided that moving to higher ground was the best action. With help from government grants and the support of the residents, the town was successfully relocated to a site about three miles away. The new town site was carefully planned to minimize future flood risks and create a more sustainable, flood-resilient community.

Could We Ever See The Great Flood of 1993 Again?

In terms of its extent, no other flooding event has come close to the Great Flood in that respect. However, in the years since, there have been three notable examples of more regional events that, for some, were even worse than in 1993.

- In 2008, the Cedar River in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, surpassed 1993 flood levels, causing widespread damage to the city and displacing thousands of residents. However, this flood was limited to the state of Iowa.

- In 2011, the Missouri River experienced significant flooding, with water levels exceeding or approaching the 1993 flood levels at some locations. Flooding also occurred along the Mississippi, however not as severe as 18 years earlier.

- The Mississippi River flood of 2019 also saw water levels approaching or exceeding the 1993 levels at certain locations, resulting in widespread flooding and damage to communities along the river. While not as extensive as the Great Flood of 1993, floodwaters remained for several months, prompting new discussions on flood mitigation measures.

While most experts agree that another flood like the Great Flood of 1993 is likely to happen and might even be made more likely by climate change, few believe another flood of that extent is likely in our lifetimes.

Regardless of when that next flood comes, the Great Flood remains a reminder of the devastating potential of natural disasters and the importance of effective flood management and community resilience. Now three decades later and in a world that seems increasingly susceptible to extreme weather events, those lessons guide our response to modern flood disasters.