Our atmosphere is constantly in motion. Weather systems are transported around the globe by this motion, with a narrow band of stronger winds called the ‘jet stream‘ providing much of this motion, which lies between cold and warm air masses.

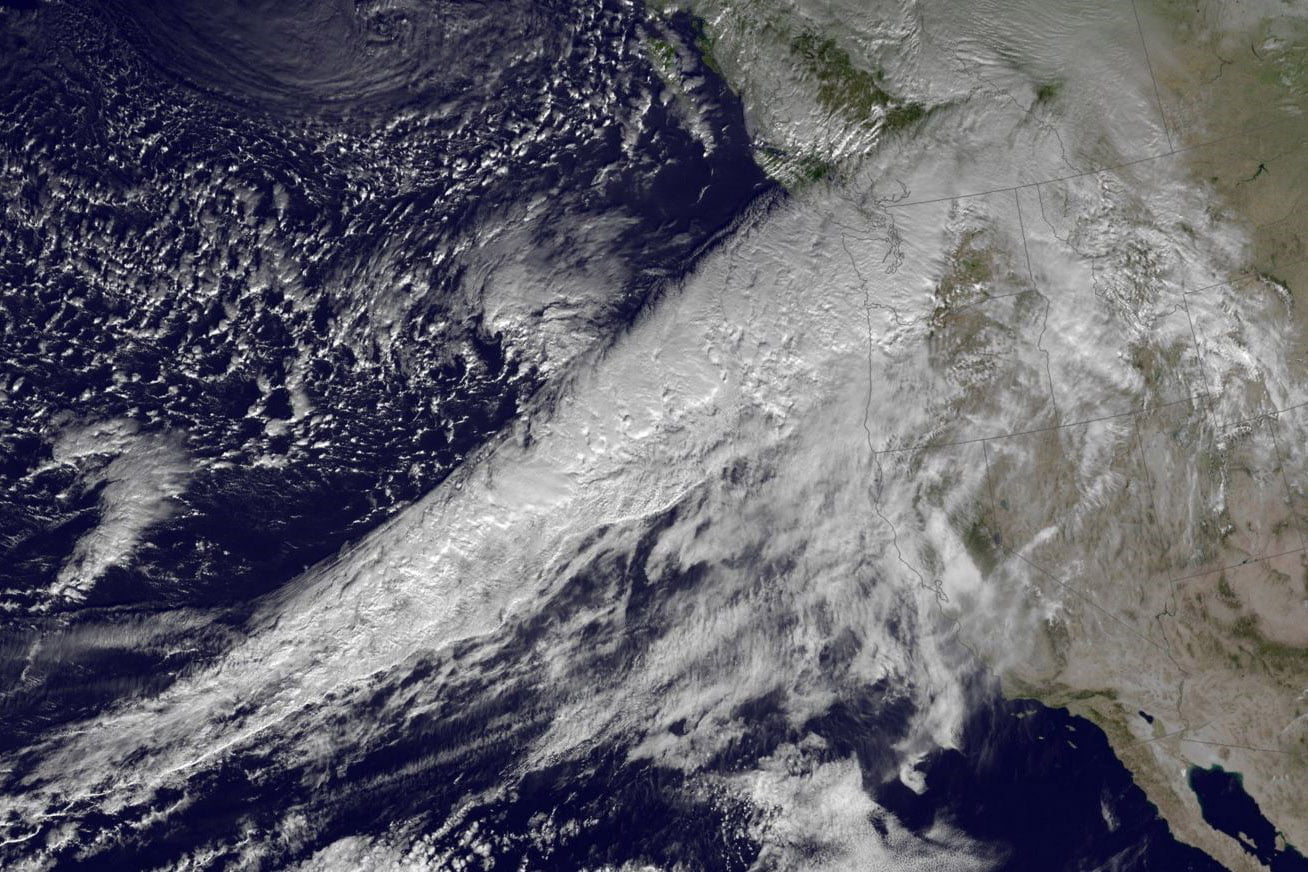

The jet stream is not a single band of winds: other smaller bands or “rivers” exist around it. One of these, which forms when the jet stream is in a specific configuration, is an “atmospheric river.” When these “rivers” of moisture meet land, the risk of heavy rainfall (or snowfall) increases if the atmospheric river gets locked into a specific position, causing flooding.

What is an atmospheric river?

An atmospheric river is a narrow band of wind that transports a large volume of water vapor from the tropics to more temperate climates. They can be several thousand miles long and only tens to hundreds of kilometers wide.

While they are most common in the winter along the West Coast, they can occur at any time of year and almost any place along the Eastern US and Gulf coasts, although they’re rarer.

The most common trigger for an atmospheric river event in the US is a slow-moving or stalled strong low-pressure system in the Gulf of Alaska, with a cold front that extends into the tropics. Winds out ahead of this front generally blow from the southwest, which provides the moisture transport necessary to form the atmospheric river.

Atmospheric rivers are not a rare event: during the winter months in the Northern Hemisphere, the jet stream’s positioning often enables efficient moisture transport from the tropics. Most of the time, this happens over water. An atmospheric river is only an issue when it comes into contact with land, such as California’s winter.

How much moisture can atmospheric rivers move?

A lot. NOAA estimates that, on average, the amount of water vapor carried by an atmospheric river is roughly equivalent to the average flow of water at the mouth of the Mississippi River!

Listen to Our Podcast on the 2023 Atmospheric Rivers

What is the ‘Pineapple Express?’

Perhaps the most well-known atmospheric river setup is the ‘Pineapple Express.’ This describes a setup that starts near Hawaii and extends to the West Coast of the United States. This long fetch of moisture produces copious amounts of rainfall (and snowfall), and it’s pretty common for a single Pineapple Express event to end droughts — especially in California — because of the amount of precipitation that falls.

Do atmospheric rivers only happen in the Western US?

No. They can happen anywhere where wind patterns promote moisture transport from the tropics to the mid-latitudes. However, they are far less common. One example was Hurricane Joaquin in October 2015. While the storm never made landfall in the United States, it interacted with a low-pressure system in the Interior Southeastern US. This allowed Joaquin to transport tremendous amounts of water vapor into South Carolina, where as much as 20 inches of rain fell in four days. Other regions of the world also experience atmospheric river events regularly during their rainy seasons.

How much rain (or snow) falls during an atmospheric river event?

Every event is different, but rain is generally measured in inches and snow in feet. The positioning and movement of the atmospheric river play a large part in precipitation amounts. A more narrow path of moisture that is relatively stationary is the ‘best’ setup for heavy precipitation since the moisture isn’t spread out over a larger area. However, these setups are rare, and most events affect a larger land area and will shift based on changing wind patterns.

It’s also worth it to note that these events aren’t always a continuous stream of moisture. Often atmospheric rivers act as corridors for storms, and an event may be the combination of several storm systems over an extended period.

Here are some notable recent atmospheric river events:

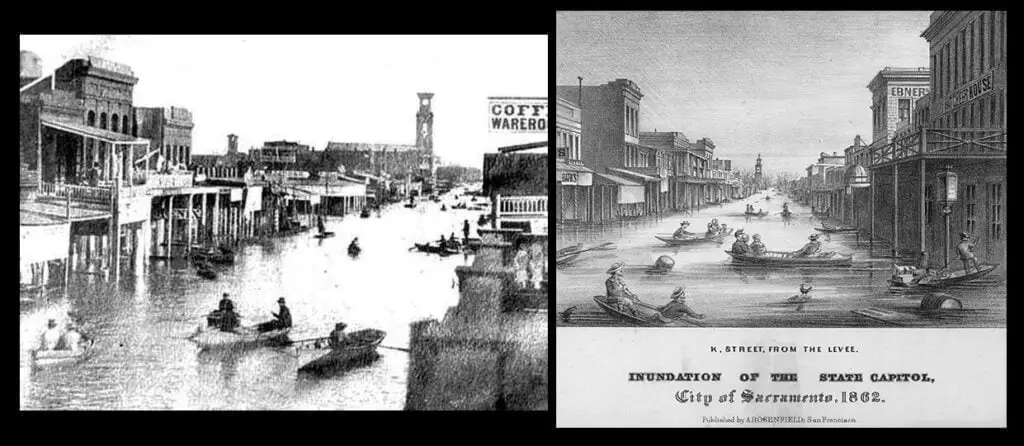

- November 1861-January 1862: A series of atmospheric river events pelted the entire West Coast for much of the Winter of 1861-62. Several feet of rain fell during the period, and nearly the entire Sacramento and San Joaquin Valley flooded, in some locations to a depth of 30 feet. To date, it is one of the strongest events, although researchers believe events of such magnitude happen approximately once every 100 years in the region.

- January 2005: A five day event in Southern California dropped copious amounts of rain, with some portions of the region, especially in the southward facing mountains north of Santa Barbara and Los Angeles seeing two to three feet of rain. The storm was followed by more than a month of near-continuous rainfall, further exacerbating the flooding.

- January 2021: An especially powerful winter storm headlined a Pineapple Express event in late January that caused widespread damage from flooding, strong winds, and heavy snow. While rains with this system weren’t as severe as other events, this event is remembered for its heavy snow and wind. Blizzard conditions across the Sierra Nevada were common, with Mammoth Ski Area recording 107″ of snow. Winds in many areas gusted to over 100 mph, with the mountain town of Alpine Meadows recording a 126 mph peak gust.

Are atmospheric rivers dangerous?

Most atmospheric rivers don’t do serious damage, with short-term flash flooding the primary threat. However, when the rains fall over the same location for days at a time, they can quickly become life-threatening.

In a powerful Pineapple Express event, flooding can last for days, if not weeks or months, such as what happened in the winter of 1861-62 (see the above picture).

California’s climate is traditionally dry, with most locations in the state seeing less than 20 inches of rain per year, with much of the southern part of the state seeing less than 10 inches annually. As a result, the ground is parched, and when heavy rains fall, the risk for mudslides and debris flows is significant. Many of the deaths attributed to these events happen in these mudslides, often with little warning.

Can meteorologists predict atmospheric river events?

While atmospheric rivers remain challenging to predict, computer modeling has improved to the point where they can at least warn of an impending event several days ahead of time. This gives residents time to prepare and, if necessary, evacuate.

The biggest issue with predicting atmospheric rivers is their position. Since these are typically narrow bands of moisture, pinpointing an exact location of the heaviest rain remains elusive. The bottom line? If you live in an area prone to flooding due to heavy rainfall, use the warning to prepare just in case.

Is climate change making atmospheric river events more severe?

Yes and no. While experts expect heavy rainfall events to increase as our climate warms, atmospheric rivers aren’t expected to increase in number or strength (although individual events may be more powerful). With climate change, researchers believe that stronger atmospheric rivers will become more common due to higher sea surface temperatures promoting more evaporation and thus water vapor in the air.

Additionally, research shows that California sees a significant event on average like that seen in 1861-62 once a century or so. Native American folklore in the region is full of stories of massive floods in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys verified through core samples and tree ring data research.